Pinyapasorn Puangjik

Patpimol Chaiyasan

Introduction

The trade relationship between the United States and China, two of the world’s largest economies, has undergone significant disruption since 2018, marked by the onset of what is commonly referred to as the US-China trade war. This period, encompassing the Trump administration’s first term (“Trump 1.0”) and extending into subsequent periods, has been characterized by two primary policy tools: the imposition of additional import tariffs and the strengthening of export control regulations. While the direct bilateral impacts on the US and China are profound, the indirect effects on third countries, particularly those in East Asia and Southeast Asia, have also been substantial. This paper synthesizes the economic consequences of this trade tension, drawing on recent research and analysis presented in the provided materials, with a focus on both tariff and non-tariff measures, their direct and indirect effects, and the strategic responses observed in affected economies. Understanding the dynamics of Trump 1.0 remains crucial for anticipating potential developments in a prospective “Trump 2.0” era.

Direct Impacts of Import Restrictions (Tariffs)

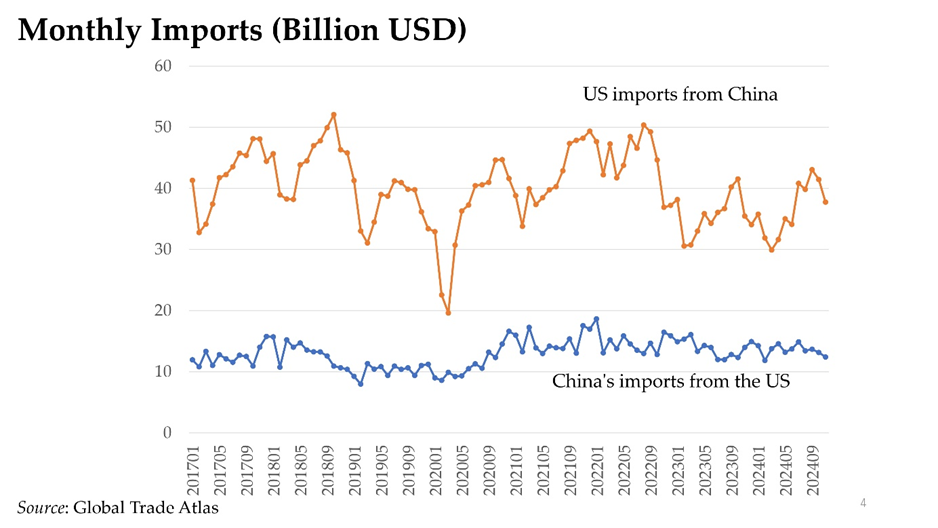

The initial phase of the US-China trade war involved the US imposing additional tariffs on Chinese goods, met by retaliatory tariffs from China. This directly impacted bilateral trade flows significantly. Academic studies show the decrease in US import values from China was mainly due to a sharp drop in import quantities, a “trade destruction effect”. This often occurred through the extensive margin, where many US importers stopped importing from China completely, disrupting supply chains. Analysis of import prices during this period revealed that unit import prices for goods from China largely remained unchanged despite the tariffs. This implied that US consumers primarily bore the burden of these additional tariffs through higher prices. Chinese firms cited already low-profit margins as the reason for not lowering price. On the Chinese side, decreased imports from the US were influenced by both tariffs and non-tariff measures. Notably, state-owned companies reduced imports from the US, particularly agricultural goods, reportedly under government direction. China also employed non-tariff measures, such as tightened inspections on US agricultural goods, the effect of which sometimes exceeded that of the additional tariffs.

Indirect Impacts on Third Countries: East Asia

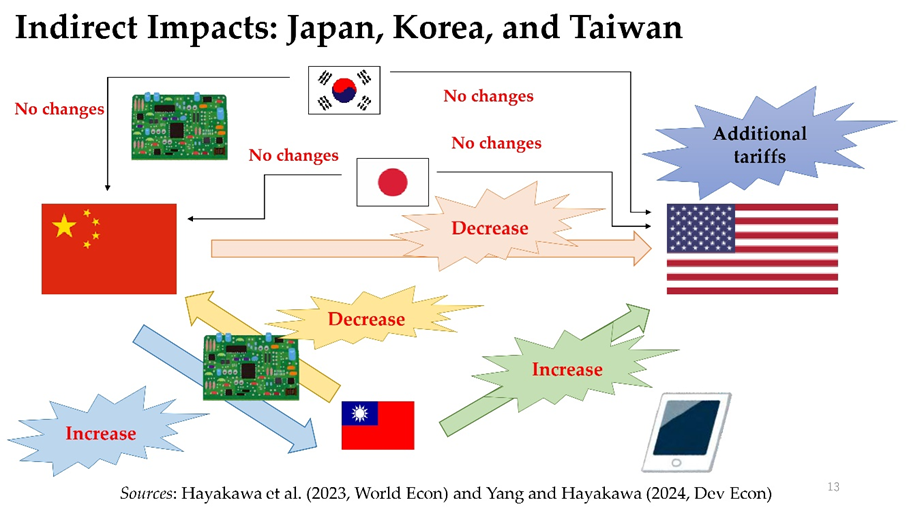

The US-China trade war had varied indirect impacts on East Asian economies during Trump 1.0 Japan and South Korea showed no significant changes in exports to the US or imports of upstream products from China. In contrast, Taiwan experienced a notable increase in exports to the US.

Taiwan’s distinct response was due to its firms’ production factories in China serving as major export bases to the US market. When faced with US tariffs on goods from China, many Taiwanese firms relocated some production lines back to Taiwan. This relatively quick relocation led to both increased exports from Taiwan to the US and continued imports of upstream products from China to support the repatriated production.

Japanese firms’ factories in China, however, primarily served the Chinese domestic market, not as export bases for the US. Their sales to North America mainly came from local production by affiliates in North America (around 73%), with direct exports from Japan being about 20%, and exports from Japanese affiliates in China being negligible (0.5%). This difference in strategy meant Japanese firms were less directly impacted by the tariffs on goods from China compared to Taiwanese firms.

Indirect Impacts on Third Countries: ASEAN and Trade Diversion

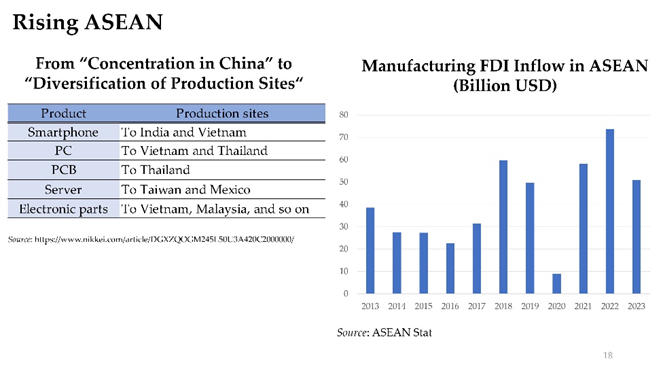

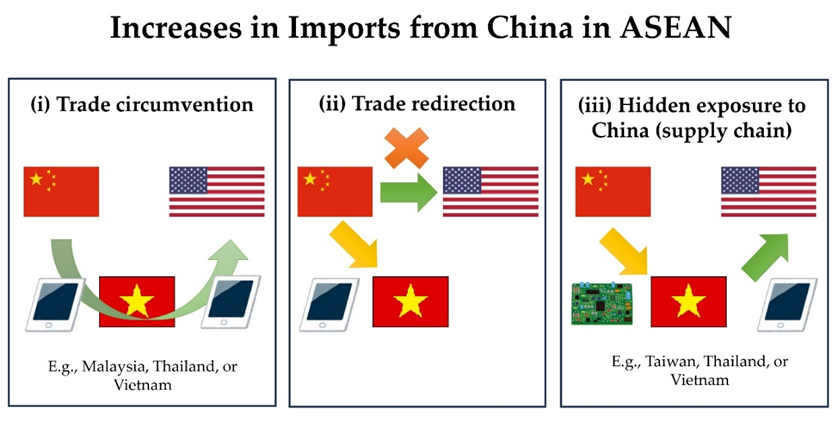

The US-China trade tensions led to trade diversion effects, benefiting certain third countries. Countries in the ASEAN region, along with Mexico, were significant beneficiaries of this in the US market. As US imports from China decreased due to tariffs, imports from ASEAN countries and Mexico increased, showing a shift in sourcing.

This shift coincided with the relocation of production lines from China to other countries. Examples include production moving to India, Vietnam (smartphones), Vietnam, Thailand (computers), and Vietnam, Malaysia (electronic parts). Several multinational firms, including Japanese, Korean, and Taiwanese companies, moved production for the US market to ASEAN nations like Thailand and Vietnam.

Significantly, studies on Thailand indicate that the firms benefiting from this trade diversion into the US market are often foreign-owned – from places like China, Hong Kong, South Korea, Singapore, the US, and Europe – rather than local Thai or Japanese firms. These foreign firms in Thailand that heavily import from China are likely increasing their exports to the US. This situation underscores the complex role of multinational firms and global supply chains in shaping how third countries are affected by the trade war.

Impacts of Export Restrictions

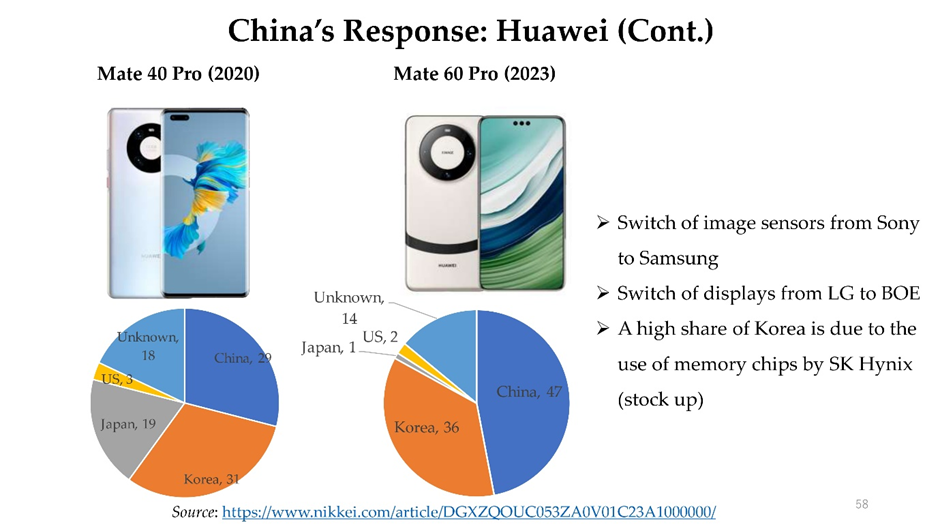

Beyond tariffs, the US has increasingly used export control regulations, especially targeting China’s access to advanced technologies, notably semiconductors. These controls are based on criteria like the item, end-user, and end-use, often imposing a “presumption of denial”. These measures have been progressively tightened. Examples include restricting Huawei and SMIC, China’s largest chipmaker, from accessing items required for producing advanced semiconductors (10nm and below). Other countries, notably Japan and the Netherlands, key players in semiconductor manufacturing equipment, have also implemented export control regulations on certain equipment to China, often aligning with US restrictions. These coordinated controls aim to constrain China’s technological advancement. China has responded to these restrictions on several fronts. For example, Huawei has increased R&D efforts and reportedly produced 7nm chips domestically. The Chinese government has also retaliated by imposing export restrictions on critical materials essential for chip manufacturing, such as gallium and germanium, where China holds a dominant position in global production.

Broader Implications and Future Outlook

The ongoing trade tensions compel countries to reassess their strategic positioning, with terms like “decoupling,” “diversification,” “friend-shoring,” and “near-shoring” being central to discussions. Diversification, generally meaning having more customers and suppliers, is seen as important for mitigating geopolitical risks, including inviting foreign firms from various countries.

Concerns exist in countries like Thailand regarding the potential for oversupply of Chinese products, particularly cheaper, lower-end goods, as Chinese firms seek alternative markets amid trade restrictions elsewhere. While imposing anti-dumping measures is an option, some suggest it might be strategically better to wait for neighboring countries to act first. Simulation results presented suggest potential significant economic impacts from future trade actions.

A simulated scenario for “Trump 2.0” indicates that the US could experience the largest negative impact on GDP (a decrease of 2.5% in 2027 in one simulation), with services potentially being hit hard. Thailand, in this specific simulation, saw a small positive GDP impact (0.1%), suggesting that while some sectors might be negatively affected (like automobiles), others might benefit from continued trade diversion.

The geopolitical context is paramount. Asian countries often aim to maintain a neutral position between the US and China, seen as the lowest-risk strategy. However, the significant role of multinational firms, which tend to follow restrictions imposed by their home countries as well as host countries, can complicate neutrality. Escalated conflicts between Western countries and China could decrease exports from Thailand to China by Western firms, while increasing imports from China into Thailand as China seeks neutral markets, potentially leading to increased trade deficits for Thailand

Conclusion

Direct impacts on bilateral trade saw decreased US imports from China, primarily driven by the termination of trade relationships and the burden of tariffs falling on US consumers, while China also restricted imports using both tariffs and non-tariff measures. The indirect effects have been significant, with countries like Taiwan benefiting from production relocation and increased exports to the US, while ASEAN nations, including Thailand, have experienced trade diversion effects, largely captured by foreign-owned firms. Simultaneously, US export controls, particularly on semiconductors, coupled with similar measures from allies, aim to slow China’s technological progress, prompting China to boost domestic innovation and restrict exports of critical materials. For third countries caught between these two economic giants, navigating the landscape is complex, demanding strategic responses such as broad diversification across trade and investment partners, addressing potential market disruptions like oversupply, and managing the implications of geopolitical risks on trade flows mediated by multinational firms. The economic future for these countries remains contingent on the evolving dynamics of US-China relations and their ability to adapt proactively through national policies and regional cooperation.

นางสาวภิญญาภาษร พวงจิก

เศรษฐกรชำนาญการ

ผู้เขียน

นางสาวพัตรพิมล ไชยแสน

นิสิตฝึกงาน มหาวิทยาลัยเกษตรศาสตร์

ผู้เขียน