Mr Mayoon Boonyarat

Mr. Ratchapol Pongprasert

The Fiscal Policy Office’s Knowledge Management Team, in collaboration with the Division of Macroeconomic Policy and Fiscal and Finance Journal, organized a special lecture on “The Role of Tax Policy in Promoting Economic Development: Lessons from Singapore’s Experience” on September 3, 2024, at the Office of the Permanent Secretary Building. This lecture featured a distinguished speaker, Assoc. Prof. Dr. Stephen Phua from the National University of Singapore who delivered a compelling presentation, sharing valuable insights into Singapore’s successful tax policies and their potential relevance to Thailand’s economic development. This article summarizes the key takeaways from the lecture.

Associate Professor from the Faculty of Law at the National University of Singapore and Director of LLM (International Business Law) program

Dr. Stephen Phua commenced his lecture by acknowledging on Thailand’s position as the second largest economy in ASEAN, emphasizing the importance of sharing lessons between Singapore and Thailand from the past mistakes to enhance regional cooperation. He then outlined the following content in his lecture. by initially providing a brief overview of the history of Singapore’s tax system and policy, He shows the Singaporean progress from the period since its independence in 1965 (SG50), explaining how these policies were instrumental in driving economic development and helping Singapore recover from four major economic crises. Secondly, he underscored Singapore’s emphasis on two fundamental principles for maintaining fiscal sustainability: revenue

diversity and expenditure restraint. He further discussed his research on the SG100 Tax Policy, noting that “what worked in the first 50 years may not work in the next 50 years… my research shows it will not work. Therefore, we need to change… we need to reform, find new sources of revenue, and find ways to supplement government revenue and spread the burden of government expenditure. These are the future challenges,” he emphasised.

1. History of Singapore Tax System and Tax Policy: SG50

For the very first topic, Dr. Stephen Phua explained that Singapore inherited a corporate tax rate of 40 percent from the British colonization era. The rate, however, plunged to 17 percent over about five decades, with an average annual reduction of 0.8 percentage points. Initially, Singapore witnessed high unemployment owing to the British military withdrawal in 1963. The government, therefore, adopted an import substitution policy, encouraging local enterprises to produce goods for domestic consumption. However, after two years as part of Malaysia, Singapore lost access to the Malaysian market when it gained independence in 1965. The country shifted to an export orientation, attracting multinationals to produce low-value goods, such as toys and simple devices.

Subsequently, Singapore restructured its economy by raising wages to advance into higher-value industries, particularly semiconductors and hard drives, aiming for long-term growth. These rapid wage increases eventually led to a loss of competitiveness, leading to Singapore’s first recession in 1985. In response, the government swiftly reduced the corporate taxes rate to 33 percent and diversified the economy into financial services to sustain the economy growth, encouraging global banks like Bank of America and Citibank to support the economy through capital markets and credit.

By the final phase, Singapore faced global challenges such as the Asian Financial Crisis, SARS, and terrorism. The country realized that relying on just two engines of growth—manufacturing and financial services—was insufficient. The country diversified its economy by developing multiple sectors—such as high-tech, education, and medical tourism—to create a long-term growth strategy aimed at consistent and sustainable expansion. He noted, “We may need twenty engines, each contributing 5%, which would provide more balanced growth between 3% and 5%, ensuring long-term sustainability.”

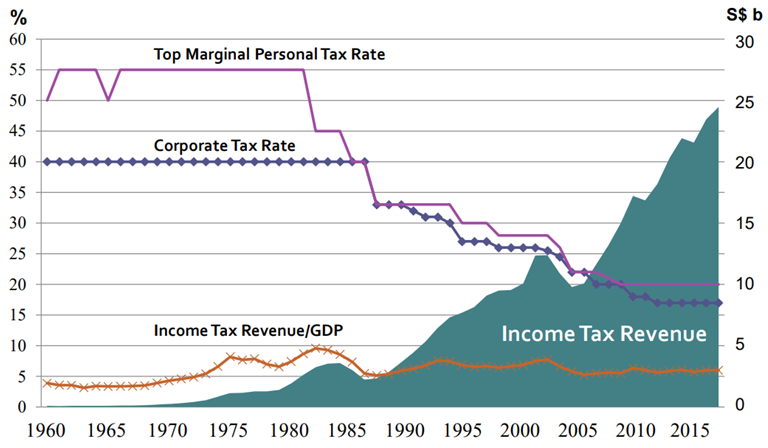

At the end of this topic, Dr. Stephen Phua also emphasized how reducing tax rates in Singapore resulted in increased revenue, aligning with the principles of the Laffer Curve theory. Singapore identified the optimal tax rate or “sweet spot” where income tax revenue significantly increased. Despite the lower tax rates, the proportion of income tax revenue relative to GDP, depicted as an orange line, remained stable. This indicates that the government continued to collect a consistent percentage of taxes for every dollar produced, without compromising profitability.

Corporate Tax Rate and Revenue between 1960 and 2015

2. Singapore SG50 Tax Policy: Fiscal Sustainability

In this section, Dr. Stephen Phua suggested that fiscal sustainability could be achieved through revenue diversity and expenditure restraint. To enhance revenue diversity, there were three approaches: 1) reducing income tax, 2) creating new taxes, and 3) increasing non-tax revenue. First and foremost, he supported reducing income tax to stay globally competitive, as many countries were moving towards lower corporate tax rates (e.g., the U.S. decreased its corporate tax rate from 35% to 21%). Moreover, he anticipated that most countries would eventually converge to a corporate tax range of 15-25% to attract and retain mobile capital, given the increasing intangibility of modern economies, which made it easier for businesses to relocate. For example, he illustrated that in Singapore, even air conditioning was provided as a service, where users were billed based on their usage rather than owning the equipment. In addition to reducing taxes, Dr. Phua also emphasized the need to introduce new tax schemes, such as GST, property taxes, and casino taxes to capture revenue from regulated activities. He also noted that the timing of introducing new taxes is critical, as demonstrated by Singapore’s gradual GST increase amid strong economic growth, in contrast to Hong Kong’s significantly failed attempt to introduce GST due to public resistance. Lastly, he underscored the crucial importance of increasing non-tax revenue by implementing fees for public services and regulatory compliance, particularly in countries with large informal economies, such as China and India.

According to the expenditure perspective, Singapore focused on careful budget management in several ways. Firstly, Dr. Stephen Phua essentially emphasized minimizing expenses and fostering self-reliance, especially as future generations influenced by Western culture might face new challenges. Therefore, Singapore maintained a sustainable tax-to-GDP ratio of 15-19%, adapting to demographic shifts. Another point was that to avoid unnecessary spending, the government prioritized saving, maintained an efficient public service, and leveraged technology to improve efficiency. Many services such as tax filings were moved online. This digital approach reduced costs and enhanced compliance with automatic penalties, promoting a tech-friendly system. Additionally, cashless transactions and online services minimized delays, while privatizing utilities and transportation eased financial pressure.

3. Coping with Past Economic Crises

For this topic, Dr. Stephen Phua identified four past economic crises, in which Singapore employed a tax system to cope with these crises. Firstly, Singapore obviously lost cost competitiveness in 1985 due to higher wages, emerging market competition, and lower foreign demand, resulting in reduced real GDP. The government responded by cutting the Corporate Income Tax (CIT) by 7 percentage points to minimize business failures. Additionally, the Central Provident Fund contribution rate was reduced from 25% to 10%, yielding significant cost savings and enabling key projects, as he noted, “the government can take on the project. Then the economy recovered in two years.”

During the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis, excessive leverage and currency mismatches, along with fixed exchange rates, caused a financial bubble. As exports plummeted and real GDP contracted by 2.1% in 1998, the government implemented tax and wage cuts, along with monetary policy adjustments, to support exports and develop a resilient bond market. This approach, combined with a tightly regulated banking system, a flexible wage structure, and a 50% cut in employer CPF contributions, resulted in rapid recovery and economic stabilization.

From 2001 to 2004, global shocks from events such as the 9/11 attacks, the Iraq War, and the SARS outbreak caused economic uncertainty. This resulted in a 1.2% contraction in real GDP in 2001 and a rise in unemployment, which reached a peak of 6.2%. In response, the government introduced fiscal measures aimed at stimulating recovery, including a reduction in the CIT rate to 20% and a decrease in personal income tax (PIT) rates. These policies helped drive economic recovery and job creation, while efforts were also made to address structural unemployment by focusing on skills matching between an individual’s skills and the requirements of a particular role, as technology began to replace traditional roles in industries such as accounting.

Lastly, in 2008, during the Global Financial Crisis, Singapore introduced the Jobs Credit Scheme, subsidizing 30% of salaries to encourage businesses to retain workers. This immediate wage subsidy provided a critical incentive for companies to maintain employment, stabilizing the workforce amid global uncertainty and supporting economic resilience during a challenging period.

4. Future Challenges: SG100

Dr. Stephen Phua went on to focus in depth on three major challenges facing Singapore’s economy. First and foremost, there was a trade-off for achieving rapid economic prosperity. While real GDP and GDP per capita surged, inequality emerged, as reflected by the Gini coefficient. Although government efforts, such as transfers and credits, maintained the Gini coefficient at 0.35, the tax system was now supporting a growing number of dependents, with fewer workers contributing to it.

In addition, the demographic shift also presented a future challenge for Singapore. Because of the two-child policies implemented in the 1970s, the nation’s aging population and low fertility rates contributed to a declining labor force, particularly noticeable in the 35-year-old age group.

To address these issues, Singapore implemented several strategies, including offering scholarships to international students to attract and retain top talent as long-term residents and workers.

Finally, he also highlighted the challenges to fiscal sustainability. The first concern stemmed from the changing social compact, where increased elderly support through initiatives like the Pioneer Package and Merdeka Generation Package had increased public expenditure. Second, structural unemployment driven by AI disruption required educational adaptations: “In law school, we implement three things: learn coding and programming, learn risk financial statement, and learn communication. So, we prepare for structural unemployment coming up.” he explained. Thirdly, half of Singapore’s tax revenue came from the top 10% of companies, which paid 80% of Corporate Income Tax (CIT). If these companies were to relocate or reduce operations, it would have plummeted to tax revenue and employment. In response, Singapore introduced new revenue sources, such as casino taxes and property taxes, to generate alternative revenue sources and boost tourism.

Associate Professor from the Faculty of Law at the National University of Singapore and Director of LLM (International Business Law) program

5. CONCLUSION

Above all, Dr. Stephen Phua’s enlightening lecture provided a comprehensive overview of Singapore’s tax policy journey, offering invaluable insights into its implications for future economic development. By sharing Singapore’s experiences, he underscored the importance of adaptability to evolving economic landscapes, maintaining fiscal sustainability, and addressing emerging challenges such as inequality, demographic shifts, and technological advancements.

As Thailand aspires to achieve sustained economic growth and prosperity, the lessons learned from Singapore’s tax policy framework can serve as a valuable guide. By implementing strategic tax policies that foster investment, innovation, and equitable wealth distribution, Thailand can solidify its position as a competitive and resilient economy in the global market.

Last but not least, I extend my sincere gratitude to Dr. Stephen Phua for graciously accepting this opportunity and sharing his expertise with young policymakers like myself. His insights into Singapore’s past experiences and future challenges have been truly enlightening. I would also like to express my appreciation to Mr. Mayoon Boonyarat, Director of Social Protection Strategy and Development Division, Mr. Chaiwat Hanpitakpong, Senior Economist at the Fiscal Policy Office, and the Knowledge Management Team for organizing this fruitful event.

Mr. Mayoon Boonyarat

Director of Social Protection Strategy and Development Division

Fiscal Policy Office

Author

Mr. Ratchapol Pongprasert

Economist at the Division of Macroeconomic Policy

Fiscal Policy Office

Author