Chanachoke Ungsrithong

Executive Summary

Purpose:

- Investigates Bangkok’s role as a primate city in Thailand’s economy and how this status contributes to spatial inequality and long-term economic challenges

Definition:

- A primate city, defined by Jefferson (1939), is one with population and economic activity significantly exceeding other cities

Spatial Inequality & Methodology:

- Economic activity and infrastructure heavily concentrated in Bangkok and the Eastern Economic Corridor

- The northeastern region, with 33% of Thailand’s population, remains underdeveloped

- Local Moran’s I spatial analysis shows economic clustering around Bangkok and weak spatial correlation elsewhere

Broader Economic Concerns:

- Thailand faces stagnant growth, declining competitiveness, and its transition into a super-aged society

- These trends are worsened and in fact may stem from the regional inequality and overcentralisation

London Case Study:

- London’s GPP per capita is 70% higher than the country’s second city

- Contributes 27% of UK tax revenue despite being 12.5% of the population

- Regional disparities in the UK have led to structural economic weaknesses

Policy Lessons:

- The UK’s “Levelling Up” policy attempted to address inequality but failed due to underinvestment and poor disbursement

- Highlights need for long-term, consistent, well-funded regional development strategies

Recommendations for Thailand:

- Invest in secondary cities, regional infrastructure, and economic decentralisation

- Avoid overdependence on a single urban hub for sustainable national development

- Thailand’s economic future depends not on weakening Bangkok’s role, but on helping the rest of the country grow alongside it

Introduction

This research paper seeks to investigate the role Bangkok has in the modern Thai economy, especially laying emphasis on the term ‘primate city’ that Mark Jefferson defined in 1939. Primate cities are cities in a country with populations and economic activity disproportionately greater than those of any other city in the country – in Thailand’s case provinces serve as the functional equivalent of cities. Some other examples of primate cities include Mexico City, Jakarta, Tokyo, Paris, and London. This topic is of particular importance because spatial disparities across and within regions have proven to be a contributor to the persistence of income inequality (World Bank, 2023) – a core issue that can lead to other economic and socio-economic challenges.

In addition to income inequality, Thailand currently faces a combination of economic challenges such as stagnant growth and declining competitiveness – all of which directly contribute to increased fiscal strain. On top of this, the country will soon become a super-aged society, which will significantly raise the dependency ratio (Paitoonpong, 2023). Notably, rising expenditures on welfare and healthcare, coupled with shrinking tax revenues from a smaller workforce will further strain the government’s fiscal capacity. To that end, a constrained budget would decrease the level of public investment possible, weakening long-term economic growth further.

While there is a declining trend in total income and consumption inequalities, Lekfuangfu et al’s (2020) preliminary investigation has found that the drivers behind this are not sustainable because of Thailand’s transformation into a super-aged society.

What is the significance of the term primate cities given this?

Countries with primate cities all significantly depend on their primate city for economic output, making large parts of their country’s GDP. In addition, this is usually where a large proportion of the population is concentrated due to the prosperity and economic opportunities it offers. As of 2024, Bangkok made up around 13% of the country’s population while around 25% of the population live within the surrounding Bangkok Metropolitan Region (Walderich, 2025). However, this overdependence on a single city for long term economic growth is not sustainable (Jefferson, 1939). Research from this paper has shown that stagnant growth, declining competitiveness and income inequality are all in some way caused by regional inequality – the overemphasis on Thailand’s primate city.

This paper offers a unique perspective on Bangkok using a case study of London, which can also be viewed as a primate city. This comparative analysis is possible from the fact that London is also the ‘economic powerhouse’ of the country, just like Bangkok is. It explores the implication of a country with a primate city in a high income economy context, offering insight into the future of what Thailand may be like. It also explores a past policy to deal with regional inequality.

The paper also explores secondary cities. As Roberts et al. (2022) argues, the performance of national economies also depends on a well functioning system of secondary cities. It is these cities that pass many of the resources, goods, and services to rural and regional areas. As a neglected area of urban policy research and development, secondary cities are therefore not maximised to their potential yet.

Primate cities

What exactly is a primate city?

Primate cities, as defined by Mark Jefferson in 1939, are the largest cities in a country with populations and economic activity disproportionately greater than those of any other city. Jefferson suggested a population threshold of at least twice that of the second-largest city, also emphasising that such cities are more than twice as significant in economic, cultural and political terms. While analysts today often use gross provincial product (GPP) to measure regional output, Jefferson’s original concept still captures the core idea of a primate city.

As of 2023, Bangkok Metropolis’ Gross Provincial Product (GPP) was 5.17 times larger than the next province, Chon Buri (NESDC, 2023) (the Gross Provincial Product per capita was 1.14 times larger). The population of Bangkok Metropolis was 3.65 times larger than the next province, Nakhon Ratchasima (ibid). This classifies Bangkok as a primate city.

Jefferson (1939) illustrated this concept when he wrote about Copenhagen, Denmark:

“ Why does the ambitious Dane go to Copenhagen? To attend the university, to study art or music, to write for the press, to attend the museum and the theater, to buy or sell if he has unusual wares or wants unusual wares. Because he keeps hearing and reading of men who live there, men whom he is keen to meet face to face. Perhaps he means to try his wits against them. Or his business capacity has outgrown his home city, and he hopes to find more opportunity in the capital, to make more money ”

Reading this, one may draw on the similarities that Copenhagen shares with Bangkok. Like Copenhagen, Bangkok draws individuals seeking education, job opportunities, and social mobility from across the country.

How did Bangkok become a primate city?

Over the past three decades, Thailand has seen stable economic growth. During the early development phases, the underlying assumption for significant investment into Bangkok was that the benefits of economic development would ‘trickle down’ to other regions in the country. The consequences of this was that the majority of resources were continuously pulled to support industrial production, which started with concentration in Bangkok (Wuttisorn et al 2014). While this led to increased industrial growth, labourers in the agricultural sector migrated toward the industrial sector in order to capture benefits of growth. As a result of this, many provincial areas were left underdeveloped and lacking a diverse workforce. Economic activity became centralised.

From the 1970s until the Asian Financial Crisis, rapid economic growth occurred primarily in Bangkok and the Bangkok Metropolitan area only. As a result, Thailand’s wealthiest have benefited the most from economic growth and there is clear evidence that inequality has risen in key areas such as education, health and political participation (Lao et al, 2019).

Jefferson had also noted another key characteristic of primate cities. He argued that once the city was larger than any other in its country, this mere fact gave it an impetus to grow that cannot affect any other city, and it would draw away from all of them in character as well as size (Jefferson, 1939). Clearly, based on the explanation above this is very much true.

Data analysis

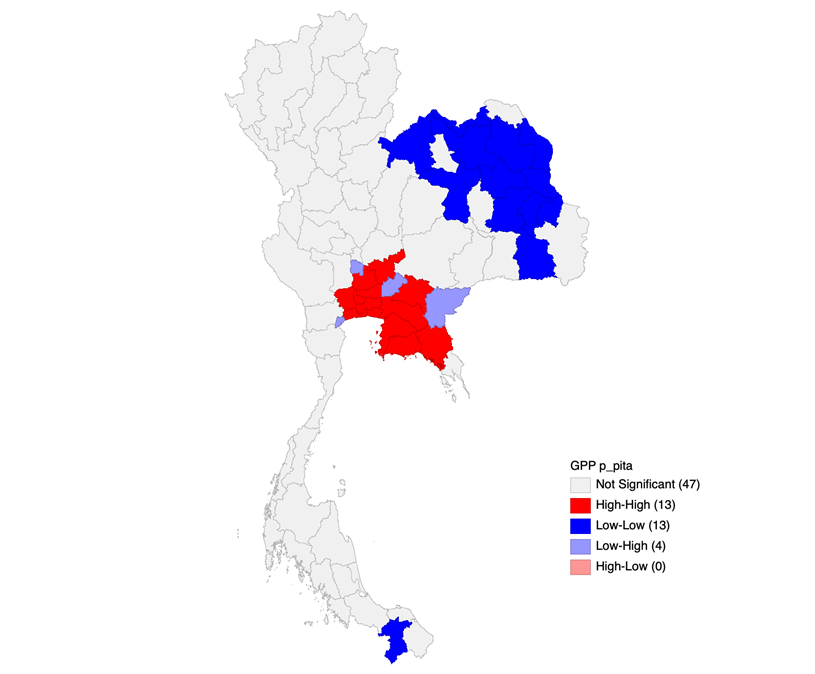

Figure 1

Through an analysis using the univariate Local Moran’s I to identify spatial autocorrelation, the local indicators of spatial association (LISA) cluster map in Figure 1 displays relationship between provinces and their neighbours. The calculation here uses a dataset of the GPP per capita of all 77 provinces in Thailand from 2023. The 13 provinces with High-High clusters are provinces with high GPP per capita surrounded by neighbors that also have high GPP per capita. The strong positive spatial autocorrelation demonstrates a regional concentration of economic activity. Naturally, these provinces include Bangkok and its surrounding Bangkok Metropolitan Region. Notably, it also includes some eastern provinces like Chonburi and Rayong, both part of the Eastern Economic Corridor (EEC).

The model found that 47 provinces’ p-value showed no statistically significant spatial autocorrelation in GPP per capita. This suggests that the majority of regions in Thailand have economies that don’t strongly influence or resemble their neighbours.

Through this methodology, it can be seen that Thailand’s economic geography is highly spatially unequal. The Bangkok Metropolitan region and EEC zone is clearly identified as economically significant, while the northeastern region remains a Low-Low cluster. The fact that the northeastern (isan) region is the country’s largest and most populous region, accounting for 33% of Thailand’s total population (Lao et al, 2019) underscores the need to ensure that growth is more equally distributed. It reveals the need for targeted regional development policies – such as using the EEC as a model.

London case study

Implications of a country overreliant on one city: Case study of London

Despite Thailand’s current status as an upper-middle income economy, it is crucial to consider the implications of continued spatial inequality as the country progresses toward high-income status. Therefore, this case study of London provides valuable insight into the core challenges Thailand is likely to encounter if regional disparities remain unaddressed. It underscores the importance for Thai policymakers to effectively address spatial inequality, drawing on the example of London’s disproportionate dominance over the UK economy. As argued by (Wright, 2013), the long standing neglect of such disparities has contributed to significant structural economic problems seen today, posing serious challenges for the British government.

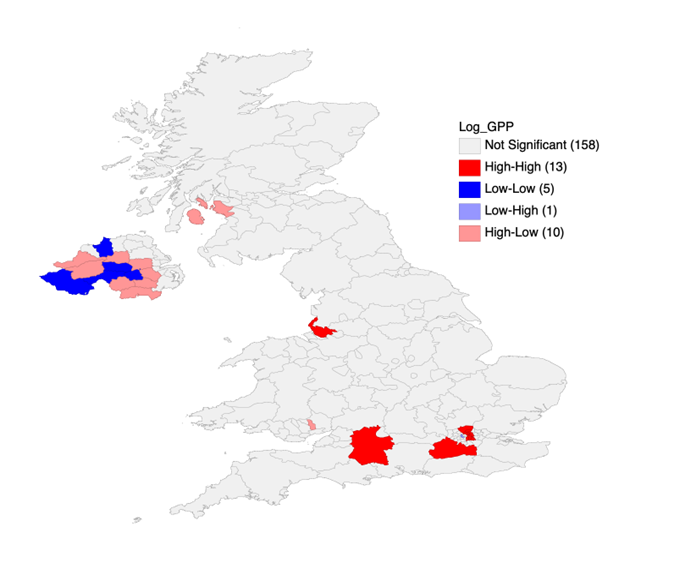

Figure 2 below is a univariate Local Moran’s I LISA cluster map of Great Britain, for the variable of log GPP per head. The majority of regions show no statistically significant spatial correlation, meaning that their log GPP per head values are randomly distributed with no clear clustering. However, there are 13 regions with High-High correlation in which the majority is located in and around London. This is one method that clearly shows London’s strong economy and high productivity spill over into surrounding areas, underlining the importance of reducing regional disparities through investment outside London to promote regional balance. This data also discredits the argument that trickle down effects will occur from London out to other cities and regions. Massey (2013), shows that London’s lead over the rest of the UK has progressively widened over the past half century and even if geographical trickle down does work, it is likely to be subject to a distance decay effect.

It is important to highlight that the regional trend shown in this map is similar to that of Figure 1, where the capital city or, in this context, the primate city has the most significant p-value.

Figure 2

Looking at economic indicators, it is evident that the UK has become overreliant on London. As put by Burn-Mordoch (2023), London is what “keeps Britain economically afloat”. In examining its significance as a primate city, previously discussed in the section above, London’s GPP per capita is 70% higher than the second largest city of Manchester (6.11 times higher in terms of GPP) (Economics Explained, 2024) – well surpassing the 2:1 threshold used. Notably, in 2024 alone, London contributed to approximately 27% of the country’s total tax revenue. This value is of particular concern due to the fact that London makes up only 12.5% of the UK population – again, highlighting the disproportionate reliance on London. Further analysis by the Financial Times, drawing on OECD regional accounts data, reinforces this even more. If London’s economic output and population were excluded from national statistics, British living standards would fall by an estimated 14 per cent. In relative terms, removing Amsterdam, the capital of Netherlands, would only cause a 5 per cent decrease, while removing Munich, Germany’s most productive city, would result in just a 1 per cent decline.

Moreover, all regions in the UK, except for London and its surrounding areas, receive more money from the central government than it contributes (Jackson, 2018). As a result of this, fiscal transfers to poorer parts of the country are effectively quite over-reliant on that 12.5% of the population. As Coady (2025) describes, for the majority of time, fiscal transfers were concentrated more on lower-income households. London, the nation’s economic dynamo, ‘the goose lays the golden egg’ (Martin & Sunley, 2023) that benefits the rest of the UK through surplus taxes paid by London businesses and residents that help to support nation-wide social and public services raises questions about long-term sustainability and also poses a real economic risk to the country.

As supported by Jolly (2021) and Hayward (2025), the logical conclusion that can be drawn from this is that for the UK to be fit for the future, prosperity must rise right across the country – this includes investment in infrastructure and skill. Indeed, it is unsurprisingly argued by Andy Haldane, then Chief Economist at the Bank of England, that unlocking the potential of secondary cities could unlock 100 billion pounds nationally, providing the much needed increase in government revenue.

Past policy: ‘Levelling up’

The levelling up policy was introduced under Boris Johnson’s government. It made redressing the balance of regional differences a central goal for the conservatives. Similar to Wright’s (2013) analysis of regional disparities in the UK, the levelling up policy was not about bringing London down, but about bringing everywhere else up – specifically addressing the North-South divide.

The levelling up policy’s mission can be characterised by four particular areas, being: 1) To boost productivity, pay, jobs and living standards 2) Spread opportunity and improve public services 3) Restore a sense of community, local pride and belonging 4) Empower local leaders and communities. The central goal of this policy was to spread opportunities across the UK so that young people would not have to leave their hometowns to succeed, simultaneously promoting growth in the ‘left behind’ regions as well.

The conservative government attributed regional wage disparities largely to differences in individual skill levels. This belief informed their emphasis on educational reform, particularly for children. Take for example the contrast between Grimsby and London: fewer than 1 in 5 children who grow up in Grimsby go on to obtain a degree, compared to the 1 in 3 children in London (IFS, 2022). Naturally, those who have attained degrees will have more access to higher income jobs and opportunities. This difference is further exacerbated by the brain drain – the loss suffered by a region as a result of the emigration of highly qualified individuals – from poorer communities (AER, 2020). In the case of Grimsby, this means that even among the small proportion of residents who attain degrees, many leave in search of better opportunities in wealthier areas. In fact, by the age of 27, half of the graduates who grew up in Grimsby had moved away.

Under the levelling up policy, the government had aimed that by 2030, the number of primary school children achieving the expected standard in reading, writing and maths will have significantly increased. In England, 90% of children will have achieved the expected standard. However, in June 2023 (last data available), only 60% of children in England met the expected standard.

Why was it a failure?

The slow pace of change speaks to the importance of long-term strategy with consistent delivery. The fundamental challenge of deep-seated geographic inequalities meant that decades of underinvestment in regions could not be fixed overnight. While the Boris government argued that shifting the existing profile of government spending to more deprived areas will itself spur levelling up, this was only applicable if billions of new investment took place which did not occur.

In addition, to just improve educational attainment without creating high-skilled jobs would almost guarantee skilled individuals would simply move elsewhere. Paradoxically, creating jobs but not providing enough opportunities for skill enhancement would lead to highly skilled individuals from elsewhere moving in, not necessarily benefiting local residents.

If Thailand continues to grow with a relatively centralised economy, the structural issues associated with the disproportionate concentration of economic and political power, similar to those seen in Britain with London, are likely to continue and worsen.

Conclusion

This paper has successfully investigated the role of Bangkok in the perspective of a primate city. It has analysed how Bangkok’s overwhelming dominance in Thailand’s economic landscape both reflects and leads to a continued cycle of spatial inequalities. Drawing on Jefferson’s (1939) original definition of primate cities and comparing Bangkok with London, it underscores the fact that an overconcentration of population, economic activity, and political power in a single city poses long-term challenges to economic development. The case study of London illustrates that even in high-income countries, unresolved regional disparities is a core problem to structural economic weaknesses and fiscal strain.

Thailand’s economic trajectory reveals many of the same warning signs including but not limited to, stagnant growth, underdeveloped secondary cities and increasing fiscal burdens. The clustering of wealth and opportunity in Bangkok and the Eastern Economic Corridor, although leading to national output, leaves the majority of regions like the Northeast economically isolated and underutilised. The univariate Local Moran’s I analysis for both Thailand and the United Kingdom reinforces this similar spatial divide, revealing a sharp contrast between high-performing regions and large areas of the country with no significant economic clustering.

The United Kingdom’s attempt to correct such imbalances through the levelling up policy is a representation of the immense difficulty of reversing decades of regional neglect. While the framework and most importantly the aims of the policy were clear, inconsistent execution and insufficient investment was the key factor for its under-targeted results. This is a particularly important lesson for Thailand to learn from.

If Thailand wishes to move into a high-income status sustainably, it must prioritise spatially inclusive development. The research from this paper has shown that strengthening secondary cities, investing in regional infrastructure and overall economic decentralisation is key to this. Doing so would not only reduce regional inequality but also unlock untapped economic potential to propel Thailand’s economic growth. Therefore, it can be argued that the success of Thailand’s economic future depends not on weakening Bangkok’s central role, but on building up the rest of the country to thrive alongside it.

Reference list

AER (2020). A Regional Approach to Reduce Brain Drain. [online] Assembly of European Regions. Available at: https://aer.eu/a-regional-approach-to-reduce-brain-drain/.

Burn-Murdoch, J. (2023). Is Britain really as poor as Mississippi? Financial Times. [online] 11 Aug. Available at: https://www.ft.com/content/e5c741a7-befa-4d49-a819-f1b0510a9802.

Economics Explained (2023). The Economy of the UK Is in Serious Trouble. [online] YouTube. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VUnAr0Msx9c [Accessed 10 Feb. 2025].

Hayward, C. (2025). Rachel Reeves must not ignore London’s vital role as engine of the British economy. [online] Yahoo Finance. Available at: https://uk.finance.yahoo.com/news/opinion-rachel-reeves-must-not-090943693.html [Accessed 6 Aug. 2025].

Institute for Fiscal Studies (2022). Levelling up: geographical inequality in the UK explained. YouTube. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PuJcuFltnB0.

Jackson, G. (2018). London’s fiscal surplus drifts further away from rest of UK — ONS. [online] @FinancialTimes. Available at: https://www.ft.com/content/31e5735e-956a-11e8-b747-fb1e803ee64e [Accessed 6 Aug. 2025].

Jefferson, M. (1939). The Law of the Primate City. Geographical Review, 29(2), p.226. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/209944.

Jolly, J. (2021). How the City became the UK’s powerhouse. [online] the Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/business/2021/feb/13/how-the-city-became-the-uks-powerhouse.

Lao, R., Parks, T., Sangvirojkul, C., Lek – Uthai, A., Pathanasethpong, A., Arporniem, P., Takkhin, T. and Tiamsai, K. (2019). Thailand’s Inequality: Myths & Reality of Isan.

Lekfuangfu, W., Piyapromdee, S., Porapakkarm, P. and Wasi, N. (2020). Myths and Facts about Inequalities in Thailand. Puey Ungphakorn Institute for Economic Research, 144.

Martin, R. and Sunley, P. (2023). Capitalism divided? London, financialisation and the UK’s spatially unbalanced economy. Contemporary social science, 18(3-4), pp.1–25. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/21582041.2023.2217655.

Paitoonpong, S. (2023). Promotion of Active Aging and Quality of Life in Old Age and Preparation for a Complete Aged Society in Thailand. Thailand Development Research Institute Quarterly Review, 38(3).

Roberts, B., Videla, J. and Nualart, M. (2022). The Regional Planning, Development, and Governance of Metropolitan Secondary City Clusters: A Case Study of Santiago and the Central Chile Region. New Global Cities in Latin America and Asia: Welcome to the Twenty-First Century.

The World Bank (2023). Bridging the Gap: Inequality and Jobs in Thailand. [online] World Bank. Available at: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/thailand/publication/bridging-the-gap-inequality-and-jobs-in-thailand.

Wright, O. (2013). We’re too dependent on London and the city is to blame, warns Nick Clegg | The Independent. The Independent. [online] 18 Feb. Available at: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/we-re-too-dependent-on-london-and-the-city-is-to-blame-warns-nick-clegg-8498789.html.

Wuttisorn, P., Lowhachai, S., Wannachart, W. and Khananurak, B. (2014). Rural-Urban Poverty and Inequality in Thailand. https://rksi.adb.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/rural-urban-poverty-and-inequality-thailand.pdf.

Chanachoke Ungsrithong

ผู้เขียน